The Matter of Sylvie Read online

Page 3

Nice teeth, Lesa thinks. Obviously kind. She likes that. The man is tall, affluently dressed, definitely ex-something: hockey player, coach, professional trainer. In the early morning light his face looks closer to forty, not the fifty she had speculated on the plane. She imagines that if she wanders down the relatively empty halls of Arrivals that he might follow, follow her into the unattended stairway leading up to Departures, or the women’s washroom, anywhere reasonably private.

Though she’d much prefer the get-to-know-you interface over a posh dinner that serves as foreplay, three glasses of red wine from a bona fide glass bottle, not the cardboard boxes with the plastic spigots that she’s used to from her boyfriend’s art show openings. But good wholehearted wine that glides down her throat, warm and smooth and heady, clouding her normally sound judgment. She feels drunk just thinking about it.

She hasn’t slept much the past few nights, the anticipation of returning home so long after her father’s death, so long a dearth of mothers. She swivels her stiff neck, her stomach churning from too many cups of coffee, watches for her red-zippered suitcase that matches her red-zippered purse. The man reaches for his briefcase with those hands, those boyish hands touching his black leather Samsonite, the real thing, no pleather here. And that’s part of it too, beyond the palpable attraction, his apparent benevolence toward Arabic-speaking mothers and shy children, is the expense/expanse of him, the possibility that someone could transport her from this Wednesday, someone so unlike her current partner.

She’s had a few partners over the course of her thirty-one years, should probably get herself a flip calendar in order to keep track of them all—though singularly, one at a time, not the habitual overlay of extramartial women that her father had over the early course of his years with her mother. Who would put up with that? Certainly not her. Still she wonders about her sculptor boyfriend, his distraction, his preoccupation with art, the openings, the art critics who cream their pants over his every exhibition: a solitary silver door suspended on a brick red wall three floors up, a suit made up entirely of flank steak, his still-in-progress burnt toast exhibit. (What does it mean? What does it say about modern society?) The constant smash of enamoured art students lounging around his studio at Emily Carr, their apartment in the West End, with their jet-black rough-cropped hair, black-mascara eyes, multi-pierced ears, their fresh, unsullied skin and slim firm bodies, male and female alike. It’s a lot to keep up with some days. Not that any of that would justify this pretty man in a blue suit retrieving a briefcase made up entirely of cow; he’s an extravagance she’s never had, never allowed herself.

The pretty man glances over, tries to make eye contact, but she’s lost in his boy-hands. She feels them on her body, her not-so-fresh but warm skin, his hands soft, kind, searching, finding something she thought she lost a long time ago. By the increasing thrum buried deep in her groin and her rabbit-quick heart, if he has to retrieve one more piece of luggage she may not need him after all.

Wednesday, July 1961 » Jacqueline, age 27

The woman from next door joins Jacqueline on the front step. She’s older than Jacqueline by twelve or twenty years. It’s difficult to guess by the woman’s pallid, flat-cheeked face and honey-blond hair. Her husband is older too, although he’s still a constable. Jacqueline’s husband is writing his corporal exam next month, and with any luck they’ll be transferred out to his own detachment. The woman is a foster mother, didn’t or couldn’t have any of her own. Jacqueline doesn’t know, has never asked, but the woman always has two or more children who rotate on a regular basis. Jacqueline sees them every three or four months, and then they, like Charles the kitten, disappear. Right now her neighbour has a set of teenaged twins, a boy and a girl who go off to summer school each morning and don’t usually come home until well after dark. Jacqueline says hello to them as she sits out on the front step after she’s managed to get her children to bed, the red ember of her cigarette glowing in the spreading darkness; there’s not much point in getting attached.

Jacqueline smiles sideways at her neighbour. Mary? Marina? Marianna? Miriam? She can never remember properly, so to be safe, she avoids the woman’s name altogether.

“Would you like a cigarette?” Jacqueline offers her a Peter Jackson.

“Thank you, no,” the woman says.

Jacqueline has to suppress a smile. The woman, in contrast to her dishevelled hair, and clearly wearing her husband’s shirt, has the manners of a queen. Then Jacqueline remembers that she is also wearing her husband’s RCMP sweatshirt. She breathes in the sweat-laden scent left by his summer skin and holds herself a moment before lighting her cigarette with a wooden match. A throng of children, hers included, although she doesn’t do a head count this time around, are on the street, playing a version of kick-the-can. They run screaming to the telephone pole with the red ribbon tied around it. There must be fifteen of them now.

“How’s your husband?” Jacqueline asks.

“He’s fine, hoping to retire soon, but with what he makes, I don’t see how we shall manage it,” the woman says.

Jacqueline nods and smiles kindly.

“Perhaps the foster children,” the woman adds. “As a source of income.”

Jacqueline hopes her husband makes corporal next month. She’s seen men older than him write their exams three, four, five times, and once they hit a certain age, the RCMP doesn’t consider them anymore. She knows there aren’t any hard, fast rules around that, but she suspects that once you are out of your prime like so many other things in life, if you haven’t already proved yourself worthy, then your chances for career, marriage, even simple companionship taper off distinctly.

The two mothers watch the pack of children whiz across the lawns, but the woman doesn’t have a vested interest in them. Instead she gazes vacantly down the street and waits for Jacqueline to initiate the next topic.

“Will you get another kitten?” Jacqueline asks.

“Charles was such a lovely kitten, one of a kind, really. My husband was especially fond of him. The special ones are hard to replace,” the woman says, looking at Jacqueline with her water-coloured eyes. So unlike Sylvie’s, this woman’s eyes have a definite bottom to them, a kind of thin hardness.

Jacqueline refrains from asking about the current set of twins. She remembers she has coffee brewing on the stove.

“Would you like a coffee?” she asks.

“Yes, thank you, I would,” says the woman.

Jacqueline gets up and goes into the house. Inside it’s so wonderfully cool and quiet, she’d like to lie down on the chesterfield for a few minutes, but of course she can’t. She has a guest on the front step, a rare occurrence.

The Pyrex on the stove is bubbling gently, making soft sighing sounds like those of a satisfied woman. Jacqueline stands a moment in the kitchen and enjoys the hushed murmur of the coffee. She looks out the window, her focus somewhere off in the distance at the ravine beyond where the children are not allowed to go. She notices a car in the alley, which in itself is not unusual; certainly cars pass through the alley all the time. But the long, sage-coloured station wagon with wood panels on the sides is stopped; she can hear the motor idling in between the sound of a radio playing elsewhere, the chickadees in among the cotoneasters with their two-note refrain, first high, then low, Be-there, Be-there. At least that’s what it always sounds like to Jacqueline, a wearisome reminder that she’s running behind and she won’t ever catch up. She stands on her toes to get a better look at the car and sees the familiar glint of Sylvie’s black hair in the bright sun. The hair on the back of Jacqueline’s neck stands on end. She feels abruptly nauseated, as if she will throw up right then and there in the kitchen sink on top of the dirty dishes leftover from breakfast and lunch that she hasn’t got to yet. She feels the bile rise in her throat. She fights it back down. Not now, not now.

As if in her dreams, helpless, she watches the man at the wheel of the idling station wagon as he kicks open the passenger do

or with his foot. She can see him clearly in the light of day: his brown brush cut, the angle of his cheeks, she registers that the right one is scarred, the blue eyes, the startling size of his extended hand that has something in it—what, she can’t tell, but Sylvie sees it and is interested. Sylvie steps toward the car door. Sylvie loves car rides. It’s her favourite thing to do. Car ride? she asks whenever she sees one pass by on the street. Sylvie go car ride?

Without taking her eyes off Sylvie, Jacqueline scans the alley peripherally. Where is Lesa? Her steadfast guardian angel, Sister Lesa? Doesn’t Lesa know a child’s safety lies in numbers? She can’t see Lesa anywhere. The man smiles widely, encouragingly. He’s saying something—Sylvie’s name? How can he know? Sylvie moves toward the smiling car, the idling man. If Lesa were there, Jacqueline could yell for her to get Sylvie and Sylvie would come. Jacqueline never raises her voice to Sylvie; it only causes Sylvie to run faster, farther away. She is afraid to open her mouth now at the screen window in her kitchen in the bright light of day, radios playing, chickadees singing, the smell of freshly mown lawn on the slight breeze, the strange smiling man, the car, her daughter.

She’s paralyzed by the fear that if she opens her mouth and a scream is what comes out, then she’ll terrify Sylvie. Who knows what Sylvie might do? Jump into the passenger seat, reach for whatever the man has in his hand, or bolt, and turn and run the other direction down the alley? Oh God, if there ever was one, let there be one now. Be-there, the chickadees scold. Be-there. But Lesa’s not there. She’s nowhere in sight.

Sylvie takes another step forward to see what the man has in his hand. She’s half in, half out of the station wagon now. Jacqueline feels the underside of her fear fall out, terror spikes through her body like an electrical charge.

“Sylvie!” she yells out the kitchen window.

Sylvie pauses, surreally, as if perched precariously at the top of the steep basement stairs over and over again like in Jacqueline’s dreams. Sylvie turns from the car and grins her crooked smile back at her mother, holding up a single red Smartie, as if to say, “See, Mom, it’s all right. It’s just a Smartie.” The man follows Sylvie’s gaze to the woman in the kitchen window, and for a brief exacting moment, mother and stranger lock eyes. Then the man smiles at her too, a smile that etches itself in Jacqueline’s mind like a pick-axe, so that when she tells it to the RCMP constable they send in lieu of her RCMP husband who couldn’t be found at the moment, nor could they raise him on the radio, then Jacqueline will tell the husband of the woman waiting for her coffee on Jacqueline’s front step right now that the man’s top two middle teeth were inverted like a V, and he had a scar on his right cheek and his eyes were blue, arctic ice.

Wednesday, February 1973 » Lloyd, age 40

After checking the farmhouse for evidence of Jimmy and finding nothing, no indication that Jimmy’s even been there in the last week, month, Corporal Lloyd swings back toward town, the street lights faint in the ashen, cold morning. Corporal Lloyd sees a car parked along the shoulder of the highway, half-assed in the shallow ditch, half not. The windows are covered in white rime. He doesn’t recognize the silver ’62 Pontiac. He slides his RCMP cruiser in behind, waits a moment, watching for movement within the car, can’t see through the heavy frost. Tries to radio the licence plates in, gets the sputter of static again. Hell, he hates to approach a vehicle blind. He’s going to have to outlaw the office altogether from his kids, who run freely back and forth between their attached house and the RCMP detachment like it’s the Wonderful World of Walt Disney.

He pulls the zipper up on his parka, gets out of the car, and walks around the Pontiac. No vehicular damage beyond the rusted-out wheel wells, the everyday dents of car door dings along the side panels. No damage to the front or rear bumpers. He peers into the back window of the Pontiac, can’t see inside. Fishes out his wallet, digs around for the “Kleenex” of credit cards, so familiar his handy-dandy Chargex, a household name, which he uses to cover the constant shortfall of his meagre RCMP salary: the credit card both curse and blessing. He clears a small patch on the car window with the plastic edge. Cups his one leather glove (he lent the other to Jimmy) around the patch, peers in, is greeted by a multitude of wide eyes. His jolt almost imperceptible, not what he expected: occupants alive, five children pressed together in the back seat for warmth, the baby has no shoes on, all flat-eyed and peering out the icy car at him.

For Chrissakes, who the hell’s in charge here?

He straightens up a moment, surveys the flat white prairies, exhales visibly in the cold February air, tries the car door, opens it slowly, carefully, so as not to scare the children. They stare out at him, their breath also visible, white, flat like the light in their eyes, the prairie landscape. All under the age of seven, Lloyd guesses. Three of them have on summer coats, the toddler is wrapped in a tattered Hudson’s Bay blanket, the shoeless baby has no socks. Corporal Lloyd removes his glove, smiles, reaches in to check the baby’s pale cheeks for life, warmth; the other children lean away from him.

“It’s okay,” he says. “Hungry?”

The oldest boy nods, the younger ones stare at him.

The baby’s cheeks barely warm.

“Best to cover this one up,” he says, taking the baby from the girl in the orange flowered summer jacket. The toothless baby smells like cardamom. He unzips his parka, tucks the baby inside, feels her bare glacial feet through the layers of his pressed beige shirt and cotton undershirt. Holding the baby against his chest, Lloyd leans into the front seat. The driver, male, approximately thirty years old, is slumped over the steering wheel. The female in the passenger seat is leaning against the window. No blood apparent on the apparent parents: no injuries, no wounds, no impairment that Lloyd can make out other than impaired; the fusty smell of last night’s alcohol strong inside the closed car. The dull eyes of children like impending victims.

“Parents?” Corporal Lloyd asks.

The older boy responds with an indeterminate nod. The toddler in the Hudson Bay blanket puts her arms out to be lifted.

Lloyd presses his lips together in a straight line, surveys the aberrant mother, glances over at the father in the driver’s seat passed out over the steering wheel, a line of still spit pooled on the man’s bottom lip, his five children in the back seat—Lloyd knows paradox like the back of his gloveless hand.

His Jacqueline at home holding down the fort; he is enormously glad for that; he probably needs to tell her that or buy her roses or something. He thanks God for the stable women, not like this one in the front seat.

One by one, he coaxes the children out of the silver Pontiac into the cruiser where he’s cranked the heater up full. He tries to convince one or two of the children to sit in the front, but the older boy insists they all sit in the back. Corporal Lloyd takes his parka off, wraps the cardamom-scented baby in it, and passes her to the girl in the orange coat. The girl grins shyly, a row of white baby teeth. He radios in once more, manages to raise Constable Pete, who responds in a thick morning voice.

“About time,” Corporal Lloyd says.

“The volume was turned off,” says Constable Pete.

Corporal Lloyd shakes his head, relays his location, the situation.

“I need you to come out here and haul these—”

Dumb asses is what Lloyd is thinking; he glances in the rear-view mirror, five pairs of child eyes watching his every move.

“Parents back to the holding cell,” he says.

“Find out who the heck they are,” he says to Constable Pete. “And call Social Services in Edmonton, they’ll want to know about this. And next of kin too. And when you’re done that, go looking for Jimmy Widman. He’s in rough shape.”

“What are you doing?” Constable Pete asks.

“We’re going for pancakes,” Lloyd says, puts the flashing lights on for fun, drives wordlessly down the highway to Neville’s hotel. He glances at the clock, nearly 9:00 AM, his shift almost done; the price of a quiet month

on this breathless Wednesday morning.

Wednesday, October 1987 » Lesa, age 31

She spots her brother, Nate, by the baggage carousel. He’s spotted her too. She’s hard to miss in her Storm getup, but he doesn’t know it’s her. She walks directly toward him. He moves in the other direction as if scanning the revolving carousel for luggage he doesn’t have. Lesa follows along behind him, almost on his heels, waiting for him to turn and tell her off, which, of course, Nate would never do. The other passengers are enormously interested, especially blue-suit man. Nate picks up his pace. Lesa stops.

“Nate!” she says.

Nate turns and recognizes Lesa’s pale face beneath the white hair. Lesa stands on her toes. God, she’s forgotten how tall he is, six-foot-five at least. Dark hair like their father, like Sylvie. She throws her arms around Nate’s skinny neck.

“Of course that had to be you,” Nate says, his face flushing.

“Oh, Nate!” Lesa lets go of him and play punches him in the belly. Nate doesn’t respond.

The passengers go back to their business of luggage retrieval. Blue-suit man cocks his head to one side, watching her. He is waiting. She lights another cigarette, glances up at Nate, who is scowling at her filthy habits: cigarettes, inappropriate airport attire, white synthetic hair, burnt toast boyfriends. She inhales her John Player Special, wishes she were special herself, a player like blue-suit man. Forget Nate, forget her waiting mother, her dead father. She wishes the man would come across the marbled floor of the airport and transport her, take her somewhere she’s never been before with his smooth boy-hands, even though she has no idea who he is—but in this fractured moment, she’s with him. No past, present, or future, simply the split second of the here and now, this beautiful, fucked-up, transitory moment that she needs to hang on to. She understands her father absolutely.

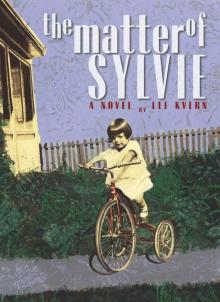

The Matter of Sylvie

The Matter of Sylvie