The Matter of Sylvie Read online

Page 4

“Who’s that?” Nate asks.

The two men watch each other.

“No one,” Lesa says, puts her burning face in her hands, peeks out at the man through her fingers like the dark-skinned child, only Lesa’s is a carnal game of hide ’n’ find. She presses her lips together in a straight, sad line, shakes her head. She is no player. The man salutes her, picks up his leather Samsonite, and goes out to hail one of the fifty identical black cars waiting alongside the airport curb. Lesa watches him go; Nate watches her.

Lesa exhales a last drag out the side of her mouth, then drops the butt onto the floor. She spots her red multi-zippered bag on the carousel and goes to claim it. Nate extinguishes her cigarette butt with the heel of his politician-helper shoes, size fifteen, hard to find; he buys three pairs at a time. He throws the flattened butt into the ashtray.

“Ready?” Nate says.

“Never ready,” Lesa says.

Nate looks at her, smiles, perhaps from relief, perhaps from her passing storm.

Lesa hefts her suitcase into the back of her non-driving mother’s Toyota. She notices something tucked beneath the outside strap of her suitcase. Scrawled across an Air Canada vomit bag: For a good time call 247-2614 ☺. Thank fuck, she thinks and stuffs the paper bag inside her purse.

Wednesday, July 1961 » Jacqueline, age 27

“Who is that?” Lesa comes into the kitchen, asks in a breathy whisper about the RCMP officer who isn’t her father but the constable from next door. Jacqueline shoos her back into the living room to watch Bugs Bunny with Nate, but Lesa doesn’t go. Instead she stands at the door and watches them at the kitchen table.

“Lesa, go out of this room now,” Jacqueline says, rising from her orange vinyl chair, her anger also rising unreasonably.

Lesa’s face crumbles as if she might cry, but Jacqueline’s fierceness keeps her in check. Keeps Jacqueline from interrogating Lesa. Where were you? How could you let your sister run around by herself ? You-weren’t-there. Jacqueline knows she’s not rational at the moment: Lesa’s five, for God’s sake. The girl is only five. She hadn’t realized how much she relied on Lesa’s help where Sylvie was concerned, but down the back alley, alone?

Lesa’s chin quivers and Jacqueline knows if she were a good mother, a capable mother, a mother who could be-there in order to keep her children safe, then she would go over and pull Lesa into her hip and run her long, curled fingernails through Lesa’s strawberry hair and tell her it’s all right, honey, everything is all right. But her legs aren’t steady and if she lets go of her chair, she’ll collapse into a heap on the kitchen floor. She can’t risk that. Lesa goes back into the living room.

Jacqueline sits down. The officer pulls out his small black book. Where is my husband? Jacqueline wants to ask. Why can’t he be reached by phone, radio? How is it possible that no one seems to know where he is? She’s never had to contact him at work before, and perhaps this is the norm, but still she finds it surreal that even the RCMP can’t track him down when she needs him most. She relays the details that have imbedded themselves in her mind, playing over and over like a looped film reel: a station wagon, sage with wood panels, eyes blue, hard blue, hands large, scar on his right cheek, inverted V on top teeth. No, she didn’t get the licence plate. Yes, he said her name. No, she didn’t hear him, she saw him. Sylvie, he said. She’s sure of that, dreadfully sure.

When Jacqueline yelled out the kitchen window the station wagon sped off, knocking Sylvie to the ground. Jacqueline ran straight into the alley and tackled Sylvie before she could regain herself and possibly take off running. She held Sylvie tight in her arms, so tight that instead of the usual squirming and flailing like Sylvie did whenever Jacqueline tried to hold her, Sylvie relinquished, relaxed uncharacteristically into her mother’s arms—a rare but fundamental hug on the gravel in the forbidden back alley.

Sylvie opened her small sweaty fist and showed Jacqueline the red Smartie that that man, Sylvie called him, she pointed down the alley to a churned-up cloud of dust, had given her. The adrenalin that ripped through Jacqueline’s body not four minutes ago turned instead to a crushing exhaustion. She sat and rocked in the back alley with Sylvie in her arms for as long as Sylvie would allow, eerily void of emotion, as if the dis-ease that coursed through Jacqueline’s veins over the days, weeks, months took over and released her from her responsibilities. Then the two of them got up and walked back into the row of identical houses.

Now, here at the kitchen table, Sylvie picks up different colours of Smarties from the bowl Jacqueline set out in order to keep her still and safe. Sylvie shows the Smarties to Jacqueline and the officer. When she picks up the red one, Jacqueline feels like throwing up again, takes a sharp breath to keep herself in check. Everything is about order, Jacqueline reasons in her mind. In order to keep Sylvie occupied, in order to keep her children safe, in order to combat the broken feeling that is welling up in her as she answers the officer’s questions. After this she must get the dishes done, prepare dinner, put the laundry away in order to get through to this evening when her husband comes home. She knows she can’t rely on him, but she can’t bring herself to think beyond this evening to tomorrow morning when the world will begin all over again, fresh with danger.

She looks at the officer and notices, despite his age, he’s firm-bodied, slightly handsome. His face is strangely unscathed, innocent even in contrast to his job, his constable status, and the state of his dishevelled wife next door and their revolving door of foster children. Odd that she never noticed this before. She doesn’t know why she notices it now, but he is sitting at her kitchen table and her husband is nowhere to be found and she finds that she needs some body, any body.

“Have you seen the man before around the neighbourhood, perhaps? The supermarket? Anywhere that you can recall?” the officer asks.

“No, nowhere. I don’t know how he knew her name.” Jacqueline pulls out a cigarette from her pack, and the officer steadies her shaking hand by cupping it with his own so she can light it. She offers him one.

“No, thank you,” he says.

He closes his black notebook and gets up. He stands a moment, gazing at Sylvie, who offers him a warmed Smartie from the palm of her hand.

“Thank you,” he says, taking the Smartie, but he doesn’t put it into his mouth. Instead he tucks the tacky Smartie into the breast pocket of his uniform.

“For later,” he says and pats Sylvie on the head as if she were his own.

Jacqueline doesn’t take her eyes off Sylvie to look at the officer. She’s afraid of what she might do.

“Mary-Lynn can stop by later if you like,” the officer says.

Jacqueline looks up, confused, then realizes he’s talking about his wife, her next-door neighbour whose name she can’t ever remember. She nods, fixes her eyes back on Sylvie; in fact, she can’t take her eyes off Sylvie. She’s terrified if she does, then something in her will break and she won’t be able to pick up the pieces to make dinner for her three children.

Wednesday, February 1973 » Lloyd, age 40

Neville flips pancakes high into the air, then onto the plates lined up across the grill. Neville’s 9:00 AM audience: two retired dairy farmers that come in every morning in lieu of milking cows, birthing calves, talking to their wives. Three bearded, black-clad men from the Hutterite colony. Eve, the hairless owner of Eve’s Beauty Salon across the street who’s undergoing chemo treatments for lung cancer, smokes her cigarettes through a long-handled holder. Five wide-eyed children with front-row seats at Neville’s counter, and the blond stranger from the bar last night sitting solo in the corner booth.

Lloyd swivels on his stool, the baby girl in his arms, runs his eyes over the blonde, who returns a Wonderful Wide World of White Teeth; she waves at the baby with one finger. Lloyd smiles at the blonde, the irony. Short of abandoning the children, who aren’t his, which the parents have already done, Lloyd can’t do much but watch the woman slip away and put the moves on the only other

eligible male in the place: Neville, not particularly catching in looks with his black oiled hair, prerequisite cook’s belly overhanging his skillet-sized belt buckle, a slap-me-go-lucky grin on his face this morning due to the blonde. On the whole, Neville is partial neither to blondes nor brunettes nor redheads but partial in general to any willing woman.

Neville sets the plates down in front of the row of children; the older ones don’t even stop to breathe before diving into the happy-face pancakes, hungry-face kids.

“Jimmy turn up yet?” Neville asks.

Lloyd shakes his head.

“He will, always does.”

“That’s the hope,” Lloyd says.

He turns back to the counter to cut up the sausages and pancakes for the Hudson’s Bay toddler swivelling on the red stool beside him.

Neville whistles the American anthem in Smoky Lake, Alberta, Canada, as he scrapes the grill.

“O, say can you see by the blonde’s early light?” He sings.

The fatty smell of fried eggs and bacon grease, glass pots of black coffee like burnt asphalt on the silver hotplates above, cigarette smoke drifting from dented metal ashtrays on the tables, from Eve, from the blonde in the corner booth, Lloyd’s cigar smoke mixing, fusing in the familial air of Neville’s café. Lloyd knows Neville hasn’t got a chance if Lloyd decides first he wants the blond stranger for later. But somehow the blonde doesn’t seem to matter this morning with a clutch of half-starved children at the counter, a baby cooing in his arms sucking on a piece of buttered toast, a babbling toddler beside him, her round mouth filled with maple pancakes. Lloyd watches Neville stride genially around the café wiping tables, clearing dishes, filling coffee cups. The two farmers, three Hutterites, Eve respond with raised eyebrows at Neville’s never-before attentiveness—anything to bask in the early light of the blond beauty in the corner.

Lloyd thinks instead of Jacqueline at home, drifting through her long days in a brightly coloured kaftan, Lesa and Nate and Clare whirling around the house, the attached detachment. Jacqueline, his steady Betty, which is what his mother called Jacqueline for the first two years they were married—Betty, an old girlfriend of Lloyd’s who his mother thought he should have married. Jacqueline gets the short end of the stick, the short straw of his mother, a double whammy. Lloyd knows he could be a better husband too. He puffs on his El Producto cigar, takes a long, slow sip of the scorched coffee.

Neville loiters at the table next to the blonde’s booth, chatting her up. The blonde responds with dark flashing eyes, those striking white teeth. She glances past Neville at Lloyd, a soft look in her eyes, too bad so sad on her crimson lips. Or is it? Lloyd looks steadily at the blonde, his own dark eyes flickering, then past her out the café window. Ice glittering like glass shards on the north wind, the grey light of morning, the grey pigeons seeking refuge beneath the eaves of the hardware store across the street next to hairless Eve’s. Despite the live wire he can feel burning, sending out shocks beneath his skin, despite the Crown Royal he craves after his shift that burns uniformly down his throat, makes him salivate like Pavlov’s dog. Despite the sweet wild aftertaste of a woman that rouses the tip of his penis, stirs deep in his groin; Lloyd makes the choice not to partake this time. Leaves her to Neville. A hotel owner goes a long way in a small town, doesn’t it? The blonde’s eyes go back to Neville. Apparently so.

Wednesday, October 1987 » Lesa, age 31

Nate stops the car in front of their mother’s house. The house is dark. Never-ready Lesa is thankful; she’s not ready to go inside yet.

“Think she’s up?” Lesa asks.

Nate shrugs.

“Don’t know why she would be at . . .” Lesa glances at the clock on the dashboard. “7:22 AM.”

Nate looks at Lesa.

“You could at least take the Storm wig off,” he says.

Lesa touches the synthetic hair.

“Later.”

Nate rolls his eyes, gets out of the car. Lesa knows Nate doesn’t get her. Why her boyfriend is a sculptor (akin to being a poet or a street busker, in the subterranean vault of the human food chain as far as Nate’s concerned.) Or why her hair is cropped blunt and shorter even than Nate’s. Or why she celebrates the hallow eve of her father’s death while Nate mourns it. Or why she resurrects Sylvie when all everyone else would like to do is forget forget forget.

“You know what?” Lesa squares her cape across her shoulders. “I’m going to go get us a couple coffees.”

“I’ll come with you,” Nate says.

“Not now, Nate,” Lesa says.

“What do you want me to tell her?” Nate sighs, stands by the car with that lost-little-boy look on his face that Lesa remembers from when Sylvie went away for good and didn’t come back. It was months before Nate quit asking their mother where she was. Lesa didn’t need to ask.

“Tell her my flight was delayed. Tell her I don’t get in until this afternoon. Tell her there’s a storm warning.”

She flashes a smile at Nate.

Nate doesn’t react. Lesa knows he’s used to her sudden recklessness.

“I’ll tell her you borrowed the car and you might bring it back in one piece,” Nate says.

Lesa climbs over the console, blows Nate a kiss. In the rear-view mirror, she sees him still standing on the curb, his beige coat flapping in the cold fall wind as she drives down the silent street her mother lives on; Nate’s shoulders slumped, his long arms hanging limp, helpless at his side.

She recalls a Second Cup in the vicinity of her mother’s house. She keeps driving north, farther north than necessary. North to Alaska, she sings in her head. North-by-northwest will take her to where Sylvie is. Where Lesa hasn’t been since they were both children; nonetheless, Sylvie is there like some sharp pebble from a residual playground in Lesa’s Hush Puppies/Adidas/stiletto boots—a problematic reminder of something she must do, something she needs to finish once and for all. What that is, Lesa doesn’t know. She only knows it’s there along with the piercing pebble of her/their youth, along with Sylvie’s soft chatter in her mind, in Lesa’s wandering days and purposeless nights at her casino job on Davie Street while her boyfriend is at his studio on Water Street, black-clad fan club et al.

She passes the Second Cup without stopping, joins the early morning rush-hour traffic on John Laurie, meanders slowly east past Fourth, then Centre Street, where most of the cars drop off and head south to downtown while she continues on. She hasn’t really thought about where she’s going other than simply away.

She merges north on Deerfoot, pulls the white wig off, runs her fingernails lightly through her hair like her mother used to when she was a kid. She wishes she were a kid again. That brief period in time when no matter what, all is forgiven; everything slips away like silk to skin, smoke to air, a magician’s trick performed by her mother. This last thought forming goose-bumps along the surface of Lesa’s freckled skin beneath the black Spandex. She knows the trick of the dysfunctional family only too well in that it leaves you lacking, looking for something that doesn’t exist. A kind of neatly packaged perfection she might find only in Samsonite luggage and smooth-handed strangers. She knows also the illusionary trick of memory: the curvature of her mother’s long nails like the curve of mother earth itself running through her child hair. The jasmine scent of her mother’s Chanel No. 5 mixed with the dark of her Peter Jacksons, the present chill in the October air.

Lesa lights a cigarette, feels the nicotine slip down her throat, fill her lungs, and then deeper she imagines, along the cylindrical walls of her veins where her blood also runs quick and deep and dark.

Wednesday, July 1961 » Jacqueline, age 27

Jacqueline looks at the gold spiral clock on the living room wall. It’s half past three. The dishes are done, laundry put away, pork chops are thawing on the Arborite countertop in the kitchen. Jacqueline managed to cajole Sylvie and Nate down into the cool basement to play Lego, or at least watch Sylvie play Lego. No one else is allowed to when

Sylvie is present, only in Jacqueline’s dreams does Sylvie share. Nate runs up and down the stairs retrieving his Hot Wheels cars two at a time from the living room, one in each of his chubby three-year-old hands. Lesa hasn’t surfaced from her bedroom since the officer left. Jacqueline starts down the hall to check on her, but again, like in the kitchen, she feels an irrational rage that she knows she can’t inflict on Lesa. She stands in the middle of the room, paralyzed. Should she call her husband again? What if he still can’t be reached? Surely they are doing everything they can to contact him? She’s not sure she can stand to hear that he’s unavailable at the moment and would she care to leave a message? She puts her hands over her face, but then Nate thumps up the wood stairs again and stops, watching her. She wipes her face and reins herself in.

“Would you like some cheese slices and apple?” she asks.

Nate nods.

“Go back downstairs and I’ll bring some.”

Nate disappears into the basement.

Jacqueline goes into the kitchen. She’s got all the doors and windows locked. The house is stifling. She slides the kitchen window open slightly while she peels apples over the sink. Outside the sun is directly overhead, the height of the afternoon heat. The air is dense and muggy, like before a thunderstorm. She avoids looking into the alley; she can still see the station wagon idling in her mind’s eye, Sylvie in the back seat waving merrily goodbye as the car disappears into the transparent waves of heat rising off the gravel. She looks instead to the sky in the west; sure enough, it’s darkening, preparing for something. She recalls the huge red sun on the horizon this morning. Really, could it only have been this morning? The day feels like months. She remembers: Red sky at night, Sailor’s delight, red sky in morning, early warning. Storm warning. Had she known, she would have locked herself and the children safely in the house for the day and made Play-Doh on the stovetop, or built Lego castles, or finger-painted, or drawn stick people in a row and cut them out and hung them like a regular family across the span of their living room wall.

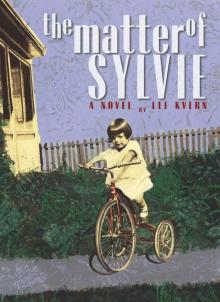

The Matter of Sylvie

The Matter of Sylvie