The Matter of Sylvie Read online

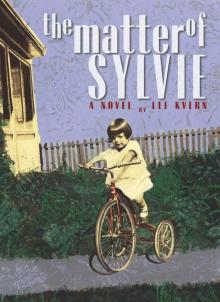

the matter of

SYLVIE

A Novel By Lee Kvern

My J. My L. My S. for being

» »

Wednesday, July 1961 » Jacqueline, age 27

The sun shimmers on the horizon, a fierce red ball so impossibly large, sailor delight or the opposite, however the saying goes, so that Jacqueline Burrows knows this Wednesday is marked already at 7:00 AM. Her children run sideways across the neighbour’s lawn in front of the row housing where she sits on the concrete step sipping cold coffee, and so later will the other wives and mothers whose husbands are also in the RCMP. The neighbourhood is a communal joke, like the joint holding cells for prisoners in the RCMP barracks in downtown Red Deer: these are the holding houses for the half-abandoned wives. Jacqueline glances down the street, but of course the other mothers and children aren’t awake. No other mother’s child rises with the first light and doesn’t go to bed until well past dark like Sylvie does. The street is quiet with the exception of Lesa, five and a half, who blurs by on her red and silver bicycle with four-year-old Sylvie perched on the back, solid like a sailor in her element. Sylvie’s scrawny arms are wrapped tightly around Lesa’s sturdy waist, her black shiny hair swinging side to side in the sun. Nate, turning three next month, races after them but can’t keep up.

“Wait,” he hollers, and Lesa pedals harder.

Sylvie turns and grins her crooked smile back at him.

Jacqueline takes a drag off her cigarette that she buys by the carton at Farrow’s Pharmacy three blocks over.

“Peter Jackson brand,” she says to Mrs. Farrow, like ordering a man. Tall, slim, dark, a non-drinker, please. The long, cool fingers of her husband, the slim hips she had before the sweet, warm smother of children, the dark dark slip of nicotine in her lungs in the early morning; the non-drinker she is, her husband isn’t.

She glances down at the pair of faded blue capris she’s got on. The hole in the right knee that she’ll have to patch when she has time, and her husband’s RCMP sweatshirt that she puts on strictly for the scent of him, to remind her she has a husband. Constable Lloyd, her Dudley Do-Right from The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show. She smiles at their bedroom joke: does she need Dudley Do-Right’s help? Dudley Do-Right will take care of that. Dudley to the rescue. Jacqueline’s shiny Canadian Mountie in a pressed dark uniform. She misses him terribly some days.

Jacqueline exhales her cigarette smoke, folds Nate’s cotton socks, Lesa’s frilled blouses, Sylvie’s plain T-shirts. Sylvie can’t wear anything with decorative buttons or embroidered daisies or fancy doodads, otherwise she worries them with her fingers and her nails, also worried down to the quick, until the offending embellishments are mere holes in her shirts and elastic-waist pants. Jacqueline piles the clothes methodically into the broken wicker basket at her feet.

Sylvie and Nate flit by, running across the row of identical lawns in front of identical houses with Lesa in tow. Only no one else along the block has a daughter like her Sylvie. The other mothers are kind, yes, sympathetic even, but not one of them really knows what a day full of Sylvie entails. So beautiful, Jacqueline thinks. Sylvie, she means, despite the cruel jagged line across both lips and her slightly off-kilter eyes. Sylvie’s face is alight, electric almost, where Jacqueline’s is laden, weighted with effort. It’s her eyes, Jacqueline decides, takes another drag off her Peter Jackson that tastes burnt; she notices she’s down to the cotton filter. If you look at Sylvie’s eyes, they are blackish-brown, bottomless really, but when Jacqueline looks at them those rare times when Sylvie isn’t ripping through the house with Nate screaming after her or tearing around the neighbourhood with Lesa at her heels, it makes her want to cry.

It’s as if Sylvie’s wires are crossed and the only time she can find stillness in this fleeting, forever life is after a seizure, which she has three, four, five times in the course of a week. Then Sylvie lies perfectly still, eerily motionless as if already dead, her dark eyes dim, vacant. Jacqueline carries her into her bedroom where a single bed is pulled well away from the window—no toys or books or pile of misshapen stuffed animals, Barbie dolls, or mess of puzzles strewn across the carpet like in Lesa and Nate’s room down the hall. She lays Sylvie carefully on the metal-frame bed and smoothes her hand across her forehead and cheeks until the colour comes back into Sylvie’s thin face, her brown eyes come back into her head. There is something wholly tangible and wounded about brain damage—like a skinned knee beneath your pressed palm. Out of sight but never out of mind. How any god can plan such ruthless things for children is beyond Jacqueline.

God or no God, Jacqueline has love enough for all her children, although the love required for Sylvie is arduous and fervent, like Sylvie herself. Different than for Lesa, who is durable, responsible; Jacqueline hardly ever worries over her. And then there is delicate Nate with his smooth child face looking up to her for guidance, approval, acceptance. His is another kind of love altogether. And it will be different again for the tiny embryo that Jacqueline knows by instinct (although she hasn’t seen a doctor yet, or told Lloyd) is growing in her uterus at this moment. The sheer thought of three children under the age of six and a new one on the way makes her slump against the screen door.

Jacqueline turns sideways and catches her reflection in the living room window. She sees an indistinct, shapeless woman, not yet thirty years old. Where did she come from? Blackened circles beneath her eyes make the once startling violet of her irises that men used to glance at twice seem a dull grey. Her hair needs another henna or it’s going to revert back to its original mouse brown. Her face, her hips are heavy with too much weight, too many children, not enough husband, she knows.

She sees Sylvie glide by the front steps; it strikes her how small, how light Sylvie’s body really is for a four-year-old. Nothing but a kinetic moving mass of legs and limbs and summer-browned skin. How can it be then that Sylvie weighs so heavily on her mind?

Jacqueline finishes folding the laundry and looks up the street. Sylvie and Nate are both on the back of Lesa’s tricycle now. Lesa struggles to push the pedals up the sidewalk to the steps. She doesn’t stop until she reaches her mother’s feet. Her face glistens with the effort. Jacqueline leans forward and spreads her arms. Nate and Lesa climb off the tricycle and stand a minute with their mother, but Sylvie sprints back down the sidewalk. Jacqueline brings the almost forgotten Peter Jackson to her lips, then remembers the burnt taste and flicks it off into the flowerbed on the side that is overgrown with three-leaf clover; she’s studied it minutely day in, day out from her outpost on the concrete steps while her children campaign the quiet street in search of fun. No four-leaf clover to be found here. She gets up. Lesa beats her to it. Running, she catches Sylvie by the arm, swings her onto the neighbour’s grass where the two girls pile on top of each other. When Sylvie gets up she is breathless and laughing. Jacqueline laughs too surprised in her tiredness, but how can she help it? Look at Sylvie, eyes dark, thrilling, her crooked mouth wide with her seal-bark laughter, her black hair shimmering in the brilliant light of early morning.

This is what Jacqueline will hold in her mind late tonight when she’s past her limit and her Lloyd isn’t home yet due to the nature of his job, due also to the fact that he can’t look at Sylvie’s skewed face, much less past it. There’s reserve, remoteness in her husband that wasn’t there before Sylvie came along that Jacqueline doesn’t understand. Where is her Dudley to the rescue? Where is her Do-Right? The space between them feels limitless, without anchor, more than she can bear if she allows herself to think about it. She doesn’t.

Jacqueline scoops Sylvie up in her freckled arms and buries her face in Sylvie’s muscled belly; she has love enough for all of them, even her absent husband. What she doesn�

�t notice is Lesa’s face, sombre and intent, gazing up at her.

Wednesday, February 1973 » Lloyd, age 40

The street is empty save for the few pigeons that fly from the hardware–post office–general store to the roof of the hotel on Main Street. Corporal Lloyd Burrows stops his RCMP cruiser in the middle of the street, fishes a leftover El Producto cigar butt out of the ashtray, lights it with a wooden match, surveys the pigeons as they shuttle back and forth. Their dull grey bodies catching the sweep of yellow street light in mid-flight, then fading away, disappearing almost in the predawn—a child’s game of Red Rover, Red Rover, we call each other over. Ice crystals hang in the still air and glitter like diminutive stars in the dark Wednesday morning.

The main street of Smoky Lake is also dark, and so is the hotel. Likely, Neville, the owner, hasn’t come downstairs yet. Corporal Lloyd listens to the crackle of the radio, indistinguishable, just a sputter of noise and static, distant voices he can’t make out, probably from the St. Paul detachment downriver. His own detachment is silent. His constables, at least the unmarried ones, are asleep in the barracks, his wife, Jacqueline, of nineteen years and children asleep in the attached house.

A quiet morning, quiet month for that matter, with the exception of the eighteen-year-old boy—almost the same age as his daughter Lesa, who will graduate from high school next year—who threw himself into the frigid waters of the North Saskatchewan River last week. Yesterday his too-young, legal-age body turned up bloated and snagged on an ice floe on Corporal Lloyd’s side of the river. Lloyd called Ed the ferryman.

“Ed?” Lloyd said.

“Corporal?”

“Yep, it’s Lloyd. Listen, Constable Pete found our boy from last week and the poor kid’s caught on our side of the river. Think you could tow it over to the other bank?”

Ed was silent a moment, in thought perhaps, weighing his answer.

“Godammit, Lloyd, you lazy son of a bitch,” Ed said. “Make Constable Pete wade in and get his feet wet.”

“There’s a twenty-sixer in it, Ed. Your choice.”

“How the hell am I going to do that?” Ed asked.

“Just do it when you only have one or two cars on board,” Corporal Lloyd said and laughed like hell.

On the other end of the phone, Ed couldn’t catch his breath from laughing.

“Let me know when you’re done, Ed, and I’ll call it into the St. Paul detachment myself and let them know they have a visitor,” Corporal Lloyd said.

“Make it Jack Daniels,” said Ed and hung up.

It’s almost 6:00 AM. The light is on in the café adjacent to Neville’s hotel. They should be open shortly. One more loop around the quiet town and Corporal Lloyd will come back and have a last cup of coffee before his graveyard shift is done at 9:00AM. The price of a small-town detachment, a good corporal, he chooses to endure the midnight shifts the same as his constables. He sits in his cruiser, motor idling, glances down Main Street—his street, his town with a population of a thousand, largely Ukrainian with a Native reserve and Hutterite colony nearby, farmers, ranchers, one doctor, one vet, a school from K to 12, two gas stations, one drive-in theatre, one wife, three—no, four children if he counts Sylvie, but he seldom does. She’s been gone so long that by rights, if out of sight out of mind means anything, Sylvie should barely graze his consciousness. But she does. The cruel imperfect line across her small lips, her dark eyes glimmering like Lloyd’s, like the blonde’s in the bar last night at Neville’s—though the woman’s were perfectly aligned, her deep russet eyes flashing at Lloyd, the all-Canadian Dudley Do-Right in uniform, who responded with a see-you-later nod, and he will see-her-later if the opportunity presents itself.

Yet Sylvie’s there too; along with the decapitated mother from the head-on collision last fall, the mother’s three-year-old child unscathed, wholly intact in the back seat of the car; the twenty-four-year-old male he found out in the middle of a farmer’s field last year, summer 1972 in a 1972 Dodge on a ninety-eight degree Fahrenheit day—a breathless, sweltering day otherwise perfect for a parade. Occupant, deceased, wounds self-inflicted.

The countless lost futures, found fingers, wallets, limbs, stray shoes and families strewn across the highway. Blue babies in car seats, cribs, on doorsteps, the bitter backs of alleys, towns like his, reserves, cities—no one place or the other immune to the colour blue. And now the legal-age boy rootless and dead in the unforgiving North Saskatchewan River; the boy old enough to make decisions, young enough to know nothing of the Wonderful Wide World of Wickedness. He’s seen that boy around town, he’s sure of it, at the hockey rink, the drive-in: graduated from high school, shoulders squared up with the world, clean-faced, a bright, dazzling future. Surely the world his oyster, at his fingertips, innocent in his eighteen-year-old hands? Welcome to life and death, Lloyd thinks. He can chase the fairness all he wants, but he knows it’ll never pan out.

Lloyd puffs on his cigar, gazes down the empty street. The north wind gusts, blows swirling snow, crystallized ice in the air, off the yellow street lights, the rooftops of Neville’s hotel/café, the hardware store, Eve’s Beauty Salon, down the dark soul-less sidewalks, the unpaved streets. Almost every lone moment he has, even now on this cold Wednesday morning, the dead and the living sit side by side like passengers in the back seat of his cruiser: Sylvie, like a live wire buried deep beneath the surface of his skin, the disquiet of an unfinished errand he can’t bring himself to attend to. And all the others? Like blood that doesn’t congeal.

Lloyd exhales the cigar smoke out the driver’s window; the smoke hangs rigid, grey in the frigid white air. It’s a disgrace, he thinks, a goddamned, cold-shouldered, undazzling disgrace, the imperfection of this world. He wipes his gloved hand across the dusty dashboard. When the sun comes up, he knows these night thoughts will dissipate. They always do, and in the few-lit hours of daylight, Lloyd will find reprieve in the salvo of a dark-lit lounge, strange women his elixir, his panacea, his magical cure.

He can already feel the perfect correction of Crown Royal in his mouth and the crimson lips of a blond stranger.

Wednesday, October 1987 » Lesa, age 31

Lesa Burrows shifts her fire-retardant cape squarely across her shoulders and watches as the plane dips down through the early morning Wednesday sky, through clouds that float like giant, murky-edged ships painted by Salvador Dali. The plane descends in time to catch the enormous sun cresting on the eastern horizon. It’s akin to descending into heaven, but of course that’s the opposite direction. The sun throws luminescent red-pink-gold light down over the green-black patchwork of the surrounding prairie where her mother lives. God-light, Lesa thinks, like those calendars you buy at Christian bookstores that show God’s translucent-truculent hand reaching down from Heaven proper, radiant fingers of bullying light bestowing the Earth with His greatness.

The thought makes Lesa want to light up a John Player Special and blow smoke rings out the window into the Dali clouds. She digs through her purse for her silver M.C. Escher case with the birds and fish morphing into one another, pulls out a John, and tucks the cigarette into the top of her Superwoman boots for later. Although the boots aren’t really super or anything special for that matter, just a pair of old fake-leather boots Lesa found in the dumpster a few years back when she was still a student at Emily Carr. Every time she puts them on she feels like young Maggie Trudeau about to go off and play polo with the Rolling Stones. Mostly the pleather boots collect dust behind the metal-fenced storage cage two floors below the apartment where she and her boyfriend, a sculptor/instructor at Emily Carr, live in Vancouver’s West End. When she gets back home, she’ll return them to the dumpster for public consumption.

She glances sideways at the other passengers drowsy in their business suits and somewhat dishevelled shirts, ties lapped loosely around their necks, ready to be knotted into action for their business meetings in downtown Calgary. At the moment, her sculptor boyfriend has a twenty-foot-high exhibition of bur

nt toast on Granville Island. The thought makes her smile, and a good-looking man in a blue suit in the next aisle smiles back. She tucks the highly flammable white wig that clings to her too-thin face behind her ears and looks out the window, senses his lingering glance. She wipes her sweaty palms on her legs. It’s almost Halloween, or at least it will be in a few days. This year she’s dressed as Storm from the X-Men for her dead father, for her younger brother, Nate, whom she knows will retrieve her from the airport. Their mother doesn’t drive. Lesa knows it’s too early for costumes, but that’s the point, isn’t it?

This is Lesa’s first time back for the memorial dinner her mother puts on every October 31 since her father died three years ago. Her father with a rare kind of cancer that devoured him slowly over the course of eleven years—from the inside out like a ripening pear, then overtly so, and no one noticed until the dark bruises appeared on his yellowing skin.

Last year for Halloween Lesa dressed up in her father’s RCMP red serge that she inherited and went around handing out Saran-Wrapped Spam (she was amazed to find you could still buy Spam) and cheese and lettuce sandwiches with a cigarette and spare change taped on top to the street people in her neighbourhood: an act of benevolence on behalf of herself and, unofficially, the RCMP. Where Nate and her mother choose grief, Lesa chooses a celebration of sorts.

She lifts her head, glances sideways at the blue-suited man. He’s older than her sculptor boyfriend but fit, conditioned like an ex-hockey player, she imagines, beneath his expensive suit. His face is even, slightly tan, a few wrinkles around the eyes, nothing to be concerned about, the beginnings of age carved into his cheeks that Lesa finds attractive, wishes she had them herself. His hair is blond-to-grey. Late forties, early fifties? But it’s his hands that Lesa is mesmerized by, oddly young. The man looks up and winks at a small, dark-skinned child playing peek-a-boo over the seat in front of him. He glances over at Lesa, who can’t stop staring at his hands, his smooth boy-hands. She smiles at him, goes back to reading the instructions on the vomit bag in the pocket in front of her.

The Matter of Sylvie

The Matter of Sylvie