The Matter of Sylvie Read online

Page 2

Lesa watches out her window as the plane slides down to meet the rushing grey asphalt and, beyond that, the city where her mother lives.

“Welcome to Calgary,” the captain says in a voice that sounds like he just woke up.

“Currently, the temperature is minus eleven Celsius.”

The passengers with ties knot them into action, take leather briefcases down from the overhead bins, pull on woollen coats. The man in the blue suit remains seated, waits as the mother ahead of him pries her child off the back of the seat, gathers her purse, a diaper bag, struggles with the overhead bin.

“Let me help,” he says, standing to release the catch, then pulling down a pink and brown overnight case, which he offers to carry, but the woman protests in another language, Arabic perhaps. Then he withdraws his canvas duffle bag that looks like it could house skates and hockey gloves, pucks possibly. Lesa stands and smoothes her black rayon cape around her Spandex, then withdraws the cigarette from her super boots, wishes it were a joint instead, and waits to disembark. She hopes her Storm will be enough to get her through this Wednesday.

Wednesday, July 1961 » Jacqueline, age 27

It’s 10:00 AM. The children have already had their lunch—Spam and cheese and lettuce sandwiches—although Sylvie has barely touched her sandwich but drained four glasses of watered-down Hawaiian Punch instead. Lesa runs back every now and then to take a bite of her sandwich, a sip of punch, and then she’s off. Jacqueline sees that Nate has discarded his lettuce into the clover patch beside the front step that she means to rescue. She peers down and sees the faint purple-blue hue of strangled violets vying for room and light among the spreading weed. Like a disease, Jacqueline thinks, dis-ease, the opposite of ease, which is how everything feels these days. Today in particular. Perhaps it’s the pregnancy, though she breezed through her others—except for Sylvie, with whom she had morning sickness from the start of her pregnancy through to the emergency high-forceps delivery because the umbilical cord was wrapped several times around her tiny neck. Jacqueline should have known that something wasn’t right.

She leans down and pulls some of the clover out from around the shrinking violets and thinks about getting down on her hands and knees, but the dis-ease inside her is pervasive, like morphine coursing leisurely through her veins until it takes over her body entirely. A pleasant enough feeling, but deep down, far beneath the surface, she senses the bottom. She knows she can’t give in to the pull. She gets up and pours the remainder of her cold coffee onto the struggling violets. She glances down the street and counts one, two, three bobbing heads in the sunlight: Lesa, Sylvie, Nate. She goes inside the house to make more coffee.

She rose early this morning when she heard Sylvie stir in the room next to hers. The light outside, not yet dawn, was grey. She spread her hand across the double bed—Lloyd either gone earlier or not home from the night shift. She can hardly keep track anymore, the days and nights meld into a slow-motion blur. She tries her best to keep Sylvie occupied in the kitchen so she doesn’t wake the other children. Lesa is a light sleeper and even the soft murmur of Sylvie’s steady rambling is enough to rouse her.

Sylvie’s dialogue is mostly directed at herself, the rare time at her mother or Lesa, when something, say, the striped orange kitten, Charles, that used to live next door and lurked beneath their front steps waiting to pounce on the children, appeared suddenly, playfully at Sylvie’s bare, tanned feet. Sylvie yelped with surprise and delight. After Charles retreated and Sylvie could no longer find him, nor spot his glowing ochre eyes beneath the dark steps, she looked up, confused, puzzled. Unease seeping back onto Sylvie’s fragile face, the familiar retreat beneath her dark eyes. But before that, the brief flicker of connection, the light on in Sylvie’s eyes, that flickered also in Jacqueline’s—with something other than the dull, protracted ache of an uncertain future.

That’s all she wants—all any mother wants, Jacqueline thinks—is to keep her children close and warm and safe. And here was her Sylvie alight and excited, in the moment—why she couldn’t stop talking and peeking beneath the steps, gesturing with both her hands that looked as if they’d been put the wrong side up on her slender wrists. But then days, weeks, seven months after Charles the kitten disappeared for good, for real this time and no one knew where, well, Sylvie still refers to it as if it happened that morning.

Jacqueline has dreams of Sylvie—articulate, lucid, standing easily at the top of the basement stairs, as if the fall that Sylvie took down the wood stairs to the concrete floor last autumn, which caused her to retreat even further from the glissant surface of her eyes, had never happened. Or else she dreams Sylvie’s in the middle of the living room floor, the sunlight slants through their picture window onto the turquoise carpet, radiant off the crown of Sylvie’s pitch-perfect black hair. Sylvie peacefully sharing her Lego, something she never does, with Lesa and even Nate, who knows better than to fight with Sylvie over anything; she’s small but has the strength of ten bears. And no one is fighting in Jacqueline’s dream as she lounges on their tattered red and black tartan chesterfield watching The Guiding Light on the television in its entirety. Her Dudley Do-Right in the kitchen preparing Swiss steak for tonight’s dinner.

Then Sylvie gets up from the Lego and comes over to the chesterfield. She tells Jacqueline that yes, she is trapped inside her body like Jacqueline suspects, and yes, her circuits aren’t right, that she knows.

“But deep down,” Sylvie says evenly, as if she’s adult now. Sylvie puts her crooked face against her mother’s freckled face so they see eye to eye like a Cyclops. “I’m here,” Sylvie says, lightly tracing the darkened circles beneath her mother’s violet eyes with her child fingers. With Jacqueline’s worst fear, her greatest joy confirmed, she looks into the bottomless pits of Sylvie’s eyes. And here in her dream, always at the same point, is where Jacqueline opens her eyes to the black of her bedroom. She can’t see a thing. Then Sylvie steps back from the waiting arms of her mother’s dreams and returns to her private world.

Jacqueline pulls the sheet up, hugs her body until the shiver down her spine up her neck dissipates, then lies flat on her back, lets the tears run themselves dry before she gets up to check on Sylvie. The residue of dream like winter’s breath lingers at the back of her mind, in the corners of her bedroom and Sylvie’s, every room in the house, everything frosted over in white.

» » »

Now in the kitchen at 10:30 AM she fills the Pyrex with water, scoops an indeterminate amount of coffee into the metal filter, and puts the glass lid on. She lights the flame on the gas stove and leans down to also light her cigarette. When she rises, she sees a gaggle of kids sprint past the back alley. She looks for Lesa, finds her among the pack, with Nate bringing up the rear and Sylvie running as fast as her legs can go alongside but not in the pack. The other children don’t know what to make of her.

“Lesa,” Jacqueline yells through the screen window.

The pack stops.

“Mom?” Lesa says.

“You know you’re not supposed to be in the back alley,” Jacqueline says.

“Ok, Mom.”

The pack takes off and rounds the corner to the front side of the street where the other mothers can see them. Jacqueline wanders back through the house. Toys are strewn across the carpet, the television is on, dancing bananas and apples—or tomatoes, she can’t distinguish between them—polka across the dusty screen. If she could only get Sylvie to watch television, even for half an hour, she could rest. She’s tired, although she suspects her weariness has nothing to do with the lack of sleep but with Sylvie, who can hardly sit long enough to eat, let alone stop and watch dancing fruit on the television. She looks at the broken wicker basket of laundry at her feet; at least the clothes are folded.

Wednesday, February 1973 » Lloyd, age 40

On his second loop around town, Corporal Lloyd turns the RCMP cruiser a block west of Main, where the streets are rough gravel. Lloyd pulls into the parking lot o

f the darkened Legion, sometimes a gathering spot for the local teenagers, although not at 6:33 AM. He sees a shadow in the entranceway and trains his bright lights on the doorway. He gets out of his car. Christ, it’s cold, minus seventeen Fahrenheit with the north wind blasting all around. He pulls his parka on and fishes his leather gloves out from the back seat, leaves the motor running and his driver door open as he walks across the lot.

“Jimmy?” he says.

The shadow doesn’t move in the entranceway.

“It’s all right, Jimmy. Come on out,” Corporal Lloyd says.

Jimmy Widman lies prostrate on the snow-covered ground. Lloyd goes over and bends down, peers into the man’s upturned face.

“Jesus Christ, Jimmy. What the hell happened this time?”

Lloyd examines Jimmy’s face in the cruiser’s headlights. He takes off a glove and puts his hand up to Jimmy’s mouth. Jimmy’s breath is cold and shallow, reeks of Wild Turkey: his choice of bourbon because it’s reasonably priced and, taken straight up, gets the job done swiftly. Also, it reminds Jimmy of his father’s farmland out east where undomesticated turkeys run feral. His father long since dead, his mother, too, by gunshot, Jimmy told Lloyd once when he was lucid, leaving Corporal Lloyd to work out the gritty details of that. No siblings that Lloyd has heard of. The wildness is all Jimmy Widman has left, Lloyd suspects. At least he’s breathing. His nose is permanently mashed to one side. And he’s missing a couple front teeth. No surprise there. He’s the resident punching bag for every disgruntled male in the town. His lips are swollen twice their size and cut. His right eye is not visible anymore and there’s dried blood, no, not dried, frozen blood pooled around his left ear. Lloyd looks at Jimmy’s hands. They are flat and stone cold but smooth-skinned as usual, not a scrape on them—unprovoked, defenceless. Another unfinished errand that Lloyd must attend to.

“The Fleck brothers?” Lloyd asks.

Jimmy smiles up at the dark and blows foul air out of his mouth like smoke rings.

“Godammit, Jimmy. Stay away from those a-holes. They’re going to kill you one of these times.”

Jimmy tries to wink with his good eye, but his eye stays shut, a foretaste of the time when Lloyd knows he will find Jimmy not only stone drunk but also dead. Just a matter of time. His puts his finger on Jimmy’s eyelid and lifts it. Jimmy’s eyeball rolls around in its socket. Lloyd pulls the flimsy windbreaker around Jimmy. He retrieves a wool blanket from the trunk of the cruiser and rolls Jimmy onto it, then swaddles him like a newborn. He zips his own parka up against the wind. Thinks about his wife and children, his constables, the townspeople at home in their warm, safe beds. He knows he can’t leave Jimmy here this time to sleep it off and eventually make his way back to the abandoned farmhouse thirty miles east of town. With the shape Jimmy in is, he’ll freeze to death before he ever figures out where his feet are, let alone how to stand up on them.

“Come on, Jimmy. Let’s get you up here.”

He lifts Jimmy under the shoulders, but Jimmy pulls a face and Lloyd suspects one of the Fleck brothers, has been trying out their steel-toed boots on his ribs. Probably broken. He’ll send Constable Pete out later to the Fleck brothers, but right now he’s going to need one of his constables to help him get Jimmy into the back of the cruiser. He slides one leather glove under Jimmy’s distended cheek and lays his head back down on the frozen ground.

“Back in a minute, buddy,” Lloyd says.

He gets in the car, radios in, waits for a response from his detachment. All he hears is static and barely audible voices from some distant place on the same frequency, no one in particular, no answer from his own detachment. Someone must have turned the radio signal down. Perhaps his youngest, Clare, fiddling with the buttons and dials, fragmented voices, the amber, red, and green lights flickering on and off like a child’s toy—despite the fact that Lloyd is a serious corporal, trying to run a stern detachment, still Jacqueline allows the children to play in the office.

He considers trying to raise St. Paul, but after yesterday’s river visitor call, he can’t very well raise them at this time in the morning and expect one of their constables to come out. He picks up his cigar butt from the ashtray and takes a puff, but the cigar is out. He pushes the lighter in on the dash. He could radio the ambulance, but the paramedics have had their fill of driving Jimmy out to the farmhouse only to have Jimmy show up three or nine hours later, however long it takes Jimmy to walk back into town. He doubts the paramedics would even come. No, he’ll swing back to the hotel and see if he can get Neville to give him a hand. Not RCMP protocol by any means but Lloyd’s small-town version of Maintiens le droit.

» » »

When Lloyd comes back, he’s got Neville in the cruiser and a Styrofoam cup of hot coffee for himself, some leftover bacon and eggs and toast with margarine that Neville hurriedly wrapped in tinfoil for Jimmy.

“Where did you say he was?” Neville asks as Corporal Lloyd pulls into the Legion parking lot.

The sun is up, but you wouldn’t know it by the thick band of grey that makes up the sky. Ice crystals in the still, frigid air now that the wind has died. Lloyd stops the cruiser in front of the doorway.

“He’s in there,” he tells Neville. “He must have rolled over or something.”

Lloyd and Neville get out of the car and walk to the entrance. Jimmy is gone. Lloyd glances across the lot, sees nothing, checks the perimeter of the low brick building. No Jimmy. He shakes his head at Neville. Neville gets back into the cruiser and lights a cigarette. He deals with Jimmy on a regular basis, lets him clear the snow out front of his hotel and the café in exchange for breakfast. Sometimes Jimmy shows up, sometimes not.

Where the hell could he have gone? Lloyd checks out the mountain of plowed snow on the other side of the lot. No one. He looks for telltale footprints, but the snow is hard and frozen; no help there. That frozen pool of blood on the cement pad where he left Jimmy lying and his leather glove is gone too. He looks up and down the empty street, then climbs back into the cruiser for warmth.

“I don’t know how he managed it. He couldn’t even keep his head off the ground.” Lloyd cranks the heat up. “His ribs are busted all to hell too. The guy must have steel balls or something,” he says, putting the cruiser into drive.

“Or wild turkeys.” Neville grins and stubs his cigarette out in the ashtray.

Lloyd doesn’t say anything.

“Want this?” Neville holds the leftover eggs and bacon up as Lloyd drives through the streets peering into doorways, down alleys, behind garages.

Lloyd shakes his head. Neville opens the foil and pulls out a strip of fatty bacon and eats it.

“I’ll come back later and have breakfast,” Lloyd says.

“I’d better get back to the hotel,” Neville says, looking at his watch.

Lloyd turns the corner and stops in front of the café. Some of the early bird farmers are at the front counter.

“Bring Jimmy round, tell him I’ll make sausage and pancakes,” Neville says and gets out of the cruiser.

Lloyd heads down Main Street to the secondary highway to see if Jimmy’s on his way home. But he’s so busted up; Lloyd doesn’t know how he could manage it. Maybe it’s the cold or the alcohol or the combination of both that enables Jimmy to pick himself up time and time again to walk back out to his father’s land when he’s had his fill of the town and its shadowy hospitality. Why he keeps coming back Lloyd doesn’t know. Neville says Jimmy’s a lost soul, hence the alcohol, the walkabouts, the strange ramblings—that Jimmy is looking for something and when he finds it, he’ll know and then he’ll be done with it. But Lloyd doesn’t think so. He’s seen it before in his small, sweet Sylvie—that inner obscure world that only she understood, and so, too, does Jimmy. It’s not the Wild Turkey; it’s something else entirely. Lloyd knows that Jimmy’s life depends on the something else.

Wednesday, October 1987 » Lesa, age 31

Lesa struts through the Arrival doors, her rayon cape

streaming/screaming out behind, exposing her athletic legs in black Spandex. She pushes back the white hair that clings to her face with the tenacity of an octopus, pulls the John out from her pleather boots and lights it. The business-class passengers veer around her, maintaining their distance, with the exception of the good-looking man in the blue suit, standing directly behind, whom she keeps in her periphery, and in return he matches her every nonchalant glance back. She takes a deep curative drag and blows the smoke out like a 1940s film star, looks around for her brother, Nate. He’s nowhere in sight, likely late as usual. Good thing he’s a genius at his job (he’s a corporate lawyer), otherwise no one would put up with the constant waiting. Waiting for Nate, she titles him, Waiting for Godot. As for the blue-suit man, she simply titles him Waiting. Waiting for a sign from her, perhaps?

The passengers stand around the luggage carousel, checking their watches every four seconds to see if they’ll make their nine o’clock meetings. Lesa wanders over to the closed money exchange kiosk, checks the current rate on the American dollar. The Canadian dollar is winning, good for her baby sister Clare, who is no longer a baby but lethal age, stunning in her looks and in Las Vegas at the moment with a pack of friends, no doubt lounging in stringed bikinis by some glittering swimming pool downing fresh lime margaritas before the sun even begins to hit its hot desert stride.

The baggage starts down the chute. Lesa drops her John Player onto the tiled floor and grinds it with the toe of her boot, leaves it there. She catches blue-suit man watching her. Yes, waiting, she thinks, based on the pleasantly charged look on his smooth face. He’s also playing hide ’n’ peek with the dark-skinned child from the airplane. The child looks out from behind her mother’s legs and when she sees his smiling face retreats shyly back until she can work up the courage to steal another quick look. The man smiles at the exhausted-looking mother.

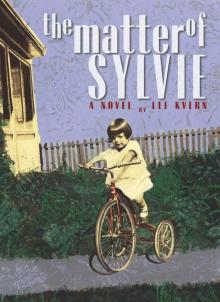

The Matter of Sylvie

The Matter of Sylvie