The Matter of Sylvie Read online

Page 7

» » »

She calculates the driving time from downtown Calgary to main-street Carstairs, roughly an hour, perhaps less given the motivated speed of Mr. Green. She parks her mother’s car in front of Hunter’s Country Kitchen (Mr. Green’s suggestion), considers changing out of her Storm getup, then decides she likes the idea of her storm blowing into a town she doesn’t know, likewise a town that doesn’t know her. She could be anyone this Wednesday morning, so unlike herself, so unlike her faithful mother to her faithless father. In her pot-addled mind she’s doing this for her mother, for all the loyal, needy/naive/trapped women out there.

Her edgy stomach reminds her that she’s hungry, needs to be attended to before anything else gets in the way. She climbs out of the car, long Spandex legs, high-heeled boots, imagines herself a spokeswoman in a sports car ad, the promise of illicit things related to neither cars nor sports. The fall air feels charged around her, sex, sex, sex flashing phosphorous orange, neon in her mind like the XXX Video store down the street from her apartment in Vancouver’s West End. Hardly the good feminist she envisions herself to be. Or the only good one, like the stunning lesbian at Emily Carr, whose feminist offence was to dress to kill, if only to torment the males that couldn’t have her. Funny. Lesa can’t make the distinction at the moment, good or bad; her stomach and charged groin won’t let her.

She walks down the street in search of a 7-Eleven or a Mac’s, any place she might pick up a bag of something salty. Two laps around the sleepy town and no fast answers in sight, she peers inside the steamy windows of Hunter’s Country Kitchen. She wonders why Mr. Green chose this place? Most likely the choices are minimal in a prairie town with the population base of a movie theatre. Or perhaps this is standard procedure for him? She doesn’t like the thought of that, prefers to think she’s unique, special. She goes inside. The $3.99 breakfast special doodled on a white board reads: Keep on the Sunny Side (with accompanying happy face), ham (loosely drawn pig), home-fires (misspelled), farm eggs (pair of amorous chickens, smiling), coffee. Four beefy men, who smell like the cattle they apparently work with, are seated at the front counter eating smiling eggs and fried pig. They pause to stare at her as she stands at the front door, waits for the lone waitress in the restaurant to seat her. The waitress waves her over to the empty booths.

Under different circumstances she could bring herself to face the men dead on, smile bravely beneath her brown freckles, but the pot conspires to make her shy, less confident, paranoid even. She doesn’t know why she bothers with it. Stopping just short of swivelling completely on their red tattered stools, the men eyeball her sidelong in her tight black Spandex, the stiletto-ness of her pleather boots, the unconscious cape she wears for her mother. She avoids their watchful eyes, and for the fourteen backward feminist seconds, the time it takes her to traverse the small restaurant, her skin jumps, crawls, bucks uncertainly beneath her storm.

She sinks down into the dilapidated leather booth, cigarette burns, minute slashes, the larger gashes patched over with ordinary grey duct tape that sticks to her Spandex as she slides across the seat. Hardly the swank restaurant, the heady chalice of expensive red wine she imagined, waiting on a man with boyish hands whose first name she doesn’t know. She can’t quell the tremor up and down her body, can’t fully decide which way to fall. Stay or go? She looks up tentatively at the four men, catches them staring at her. They nod, smile politely beneath curled moustaches, heavy brows, John Deere ball caps, go back to their coffee and home-fires.

The waitress plonks a handwritten menu down on the table; the host of greasy fingerprints make it almost illegible. The waitress splashes black, burnt-smelling coffee in Lesa’s white cup, shifts from one ample hip to the other and back again while Lesa peruses the menu.

“Whaddya have, honey?” she asks.

“The special, please,” Lesa says.

“Whaddya have on there?” the waitress asks, pointing at her costume with the end of her chewed-up Bic pen.

“Storm?” Lesa tries.

The waitress shakes her head.

“Don’t know it. How do you want your eggs?”

“On the sunny side,” Lesa says, tries to suppress the stoned, ironic grin creeping onto her face.

“White or brown toast?”

“Brown,” Lesa answers.

“Bacon, ham, or sausage?”

“Bacon, crisp.”

“Hash browns or home fries?”

“Home-fires.”

The waitress busy with her order pad doesn’t respond.

“Cream?”

“Black.”

“Those are some nice black boots,” the waitress says, admiring them momentarily before she picks up the menu, goes back to the counter, and pours a round of five-cent refills for the four men. Lesa can hear the waitress explaining, “Some storm from somewhere, who the hell knows?”

Lesa sips on the burnt coffee, looks around the rundown restaurant at the fake wood panelling identical to what her mother had in their basement in the late 1970s. The supposed good years, the heyday, when she and Nate had moved out, seeking their own places. Nate across the country in Ottawa, Lesa in Vancouver. Teenage Clare technically still at home but hardly there. When money and time opened up after all those difficult, intense years for her mother raising children, followed by a decade of caregiving for her father, who by then was bruised, yellow-skinned, terminal, sitting faithfully in his La-Z-Boy chair smoking thick, odorous cigars. Her mother went on aging two-fold while her father died too young. And here now in 1987, the good years long past, her father gone, her mother alone, Clare moved out, the fake wood panelling in their basement hasn’t changed one iota; atonement, it seems, for no one.

Lesa’s muddled mind runs the gamut: her sculptor boyfriend preoccupied with steak dresses and burnt toast, her lonely mother, her faithless/fateful father, and now this morning Mr. Green at the airport, like a soft, shimmery thing out of nowhere, someone who cares. Or so she hopes. She imagines his kind eyes resting on her flushed face, can feel the sure-man touch of his boyish hands, one swift, single moment, repealing not only her mind-numbing presence, but also the irretrievable future. What then? What of her boyfriend? Her mother? Dead father, disappointed brother? Reversible/irreversible? She looks up from her reverie, sees the men from the front counter watching her with renewed interest. Does her face tell what her mind is revealing at this moment? She hopes not.

The waitress sets the platter of crisp bacon and greasy eggs and home-fires down, pours more black coffee into her cup. Lesa dives in, glad for the diversion, surprised by her sudden need to hurry, her overwhelming hunger, her wavering mind clearing, solidifying with each bite, each gulp, hardly a stray thought as she devours her Keep on the Sunny Side breakfast special.

She takes a last sobering slug of coffee, leaves a ten-dollar bill on the table for the five-dollar tab. The waitress picks it up.

“Need change, honey?” she asks.

“Not from you,” Lesa says.

Lesa unsticks her Spandex from the duct tape as she slides across the superficial gashes on the booth seat. She doesn’t need to know Mr. Green’s first name. It doesn’t matter; what matters is that she gets the heck out of Dodge before he appears and then everything goes sideways, stormy, irreversible, irretrievable.

Time yet, she thinks, the time her father didn’t get. She’s doing this for him.

“Bless you, darling, have a good day,” the waitress hollers across the restaurant. The four men nod. Good God, she’s trying.

Wednesday, July 1961 » Jacqueline, age 27

It’s 8:30 PM. No word from her husband. How is that possible? Jacqueline is exhausted. Her head is woozy. She realizes all she’s eaten today is Sylvie’s leftover Spam and cheese sandwich from early this morning. From then on it’s been a steady flow of Peter Jackson, the man she should have ordered, and black coffee. Likely the heat and lack of food and Jacqueline’s nausea are the cause of her light-headedness, and because of it, she

allows herself a treacherous game of what if ? What if she hadn’t gone to get coffee for her neighbour at precisely that moment? What if that man had managed to pull Sylvie into the car? What if her husband doesn’t come home tonight? What if this unrelenting nausea means another Sylvie? Oh, God, she can’t think about that. Her hands shake uncontrollably as she picks up Lego from the carpet covered in Nate’s sticky vomit.

“Two more hours,” she says out loud to herself, to Nate, who is sprawled out on his back on their tattered black and red tartan sofa in a fresh white T-shirt and Superman underwear, asleep. Exhausted after the vomiting, his bath. Two more hours, then perhaps when the late July sun goes down, then so will Sylvie, who is safely at the kitchen table right now filling her sheet of blue-lined paper row by row, line after line with minute circles in circles that she draws with a ballpoint pen until the entire sheet is full on both sides. It’s one of the few things Sylvie can sit still for, on a good day sometimes for two hours. At least she’s not sprinting about the house. Jacqueline lets her be.

Lesa is in her room. She came out long enough to occupy Sylvie while Nate was vomiting, long enough to slather a piece of Wonder Bread with peanut butter and then disappear back into her room. But not before Jacqueline retrieved the two glass doorknobs and screwed them securely into place so Lesa could neither lock herself in nor her mother out, whatever the intent.

Jacqueline looks up from the sticky-sick Lego and on the muted television sees Ethel and Lucy dressed in factory clothes at a conveyor belt, wrapping the candy as it comes down the line, then as the conveyor belt speeds up, Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths, their hats, down their shirts. Despite her fatigue or because of it, Jacqueline laughs until her eyes water. Coincidentally, it’s also Lesa’s favourite show. Jacqueline wonders if she and Lesa are more alike than she realizes. She goes down the hall to tell Lesa that while she doesn’t normally get to watch I Love Lucy because it’s past her bedtime, as a special treat, she can tonight. Lesa is lying sideways on her bed, still dressed in her plaid skort and pink-frilled blouse from this morning. The heat less so now, but still warm and ominously close, like before a thunderstorm. She’s staring up at the swirl plaster ceiling.

“Lesa?”

She doesn’t answer.

“You Love Lucy is on if you’d like to watch it,” Jacqueline says, smiling at Lesa.

Jacqueline walks across the room and sits on the edge of the bed. She puts her hand on Lesa’s back. Lesa doesn’t move.

“Lesa, Mommy is not mad at you,” she says, meaning to explain this afternoon, Sylvie, the officer, although the stiffness in her voice contradicts her. And there is no denying the sudden fury building unreasonably, coursing through her at this moment. Why does she feel this way? Lesa sits up and looks at her keenly. Jacqueline knows the ball is in her court. Of course it is, she’s the adult here, but she can’t read Lesa’s lightly freckled face. Accusing? Forgiving? Or is it beyond-her-age understanding? She doesn’t know. Lesa’s strawberry-blond hair is fine but messy, so very different than Sylvie’s flawless black glimmering hair, as if God intended that to make up for the rest of it. Jacqueline would like to reach out and smooth down the perpetual rat’s nest at the back, and hold Lesa and tell her she loves her, but she’s afraid to. Jacqueline knows the brink; she’s been there before. Once, she couldn’t calm Sylvie, who was shrieking uncontrollably in her crib. She shook her twice, three times, then the realization hit her that this was where a mother ceased to be a mother and became something else instead—an unintentional monster. She removes her hand from Lesa’s back as if she’s on fire. Lesa can’t, won’t understand, Jacqueline thinks. Lesa’s unwavering green eyes hold her gaze, waiting for her to be a mother instead of the monster she feels growing inside.

Jacqueline stands up abruptly and leaves the room without saying a word. She locks herself in the washroom. The faint smell of vomit still in the air. She ignores the mushroom gravy spewed over the toilet and the blue bathmat and closes the cracked lid and sits on it, smokes a cigarette, smoothing out her serrated edges, until the dis-ease takes over once more and flatlines her into the null and void.

In the living room Jacqueline leaves the television on even though I Love Lucy has already ended and Lesa didn’t come out. Jacqueline thinks about going to check on her, but then thinks it may be better to let sleeping monsters lie. They can discuss it in the morning when everyone feels better.

After she’s done picking up the Lego and scrubbing the spray of vomit as best she can from the turquoise carpet, Jacqueline looks over at sleeping Nate. She’d forgotten about him. She looks at his gangly, sun-browned limbs splayed out in complete and utter abandonment as only children can do. She resists the urge to go over and bundle him up in her arms and nuzzle his skinny neck that looks as if it can’t possibly support his toddler-large head but does. She knows eventually his body will grow into it. But for now, all she wants to do is tuck her children safely beneath her arms and keep them there forever, if that’s what it takes. She covers Nate lightly with a clean bath towel. She’ll put him to bed shortly, and hopefully Lesa will be asleep too.

She carries the bin of Lego down the hall to the bathroom. She peers into the kitchen to see that yes, Sylvie is at the kitchen table, her chicken-wing shoulder blades jut out, mere skin over bone as she hunkers over her drawing, absolutely absorbed in the moment. Jacqueline pauses, mesmerized by the extraordinary power of focus and stillness that Sylvie finds only in drawing. And Jacqueline imagines beyond Sylvie’s scarred lips and crooked dark eyes that if Sylvie were normal, she could grow, as Nate will into his head. But in a less tangible way for Sylvie. In a way that includes a future, what every mother wishes for her children: chance, choice, possibility. Perhaps Sylvie could build a serene life as an artist, instead of this trapped, frenetic existence: all crossed wires and misfiring neurons. Jacqueline tiptoes across the linoleum, careful not to disturb Sylvie from her reverie, and peers over her shoulder: an entire sheet of meticulous rows of faultless blue circles. Jacqueline doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Wednesday, February 1973 » Lloyd, age 40

Lloyd drives swiftly through the town to the small brick courthouse. Stationary smoke from the metal stacks hangs like exclamation marks above Neville’s! Eve’s! the hardware store! Hardly a soul on the cold street as Lloyd takes the courthouse steps two at a time. Staffing the front desk is Doris Michelchuk, former town council, egg farmer, hair the colour of a chocolate soufflé teased up high like a country singer. Corporal Lloyd waits until she stops typing.

“Judge Wade around?” he asks.

Doris goes through the pretense of checking the day’s Rota. Doris is adept at knowing precisely where everyone in the town is at any given moment of the day, but she checks anyway.

“Nope,” she says, closing the book. “He’s not here at the moment.”

“A little under the weather, corporal?” she asks.

“All in today, Doris.”

Doris shakes her brown unmoving mass, purses her orange lips.

“He stepped out,” says Doris.

Lloyd waits. Doris goes back to clattering on her Smith Corona.

“Heemno,” she says under her breath.

Lloyd smiles. Ukrainian for shit.

She stops typing.

“He’s over at Neville’s,” she says.

“You’re a prize, Doris,” says Lloyd, winking at her.

Doris pulls a bottle of correction fluid from the desk drawer.

“You’re welcome,” she says, watching Corporal Lloyd exit the building and jog across the street to Neville’s, leaving his cruiser parked out front of the courthouse.

Neville’s lounge smells musty: dank, festering yeast. The bar dark in the middle of the day, so the patrons don’t have to be reminded that this is also the middle of the week. When they should be at work instead of killing the daylight hours in a darkened lounge sitting around beer-soaked terry-cloth tables—the festering decay of We

dnesday. Lloyd squints into the dim room, finds Judge Wade holding court in the back along with a couple of the paramedics, no doubt the smartass on the radio earlier who never showed up, the night security guard who speaks mostly Ukrainian, fractured English. Lloyd hires the security guard whenever he has a special guest in his holding cell—not the infrequent townsfolk gone off on the occasional funk. But special, like the guy they picked up for a broken tail light on his Chevy truck. Corporal Lloyd and Constable Pete not impressed when they had to chase the bastard over three miles of farmers’ field, through a swamp, and then into a prairie slough for a broken tail light? Even less impressed after Constable Pete tackled him, and Corporal Lloyd cuffed the man’s hands behind his back, and they took him back to the detachment. The three of them covered in sheep shit and quagmire from head to Strathcona boot to find out the guy was wanted on a Canada-wide warrant for killing his entire family. That kind of special.

Lloyd walks over to the table, ignores the paramedics, turns his attention to Judge Wade: fat slab of a man, a large heart of silver quarters that he doles out to Lloyd’s kids like a Vegas slot machine every time Lloyd throws a poker party in the concrete basement of his house. Judge Wade is the real thing. Genuinely cares through thick and thin, cases that make you cringe, and worse, the cases you couldn’t make up that make your head reel, your stomach sick, make that first shot of Bacardi’s, Crown Royal, Glenfiddich, and the taste of strange women, sweet and necessary; to everyone their niche. The judge’s niche: Southern Comfort in Lloyd’s northern town.

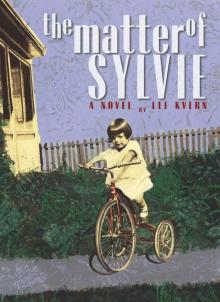

The Matter of Sylvie

The Matter of Sylvie